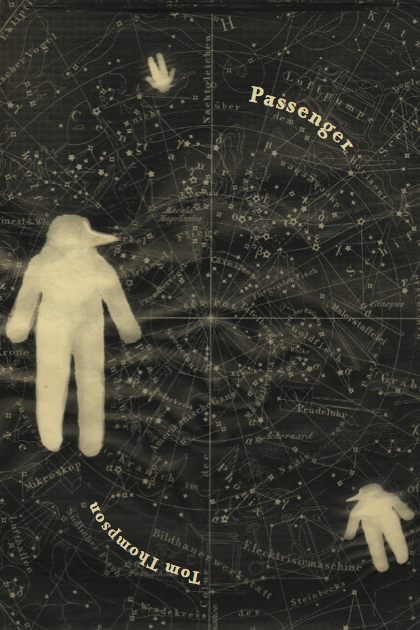

ON SALE NOW

-

With radical hospitality and good, dark humor, Tom Thompson encourages a care for the world and the imagination in ways that few other poets do, in ways I never thought (in Dickinson’s word) ‘possibler.’ He’s one of my favorite writers, and it’s a pleasure to know what he has to say.

Graham Foust -

In this, Tom Thompson’s amazing new collection, the ‘passenger’ of the title is, among other things, consciousness, ‘a new state of nature/to which our bodies are ill-adapted’; it is also the body itself, for which the reverse of Thompson’s formulation also holds true: our relationship to the body is portrayed herein as problematic and mediated, as if we have found ourselves passengers venturing through life in a strange vessel. Among other things, Thompson presents, in hallucinatory images, how modern medical technology is not so different from the occult violence and sinister paraphernalia that have always attended upon the rituals of healing. The book’s passengers go on journeys that are visionary and sometimes disillusioning: through parenthood, faith, illness, death and love; intervening in and altering the lives of living things, from children to geraniums. Passenger is a beautiful and moving book by a masterful poet.

Geoffrey Nutter -

Tom Thompson’s Passenger is a complicated, possessed portrait of the storms that inhabit, course through, and animate our minds, in and out of time. This is ultimately a book of spiritual questioning in which the boundaries between self and other, mind and body, time and timelessness do not hold. Boundaries blur because the speaker is both actor and acted-upon. Images of hospital machinery and the mind as a kind of machine–a disordered and strangely miraculous machine–proliferate: ‘Turn me // one notch down, please,’ the speaker says. ‘My head’s full of furze.’ We are both inside and outside of ‘the noise machine we calibrate to Bardo panic.’ I’m especially stung by Thompson’s descriptions of the body, which is at times ‘one shallow piece of skin // an alien, / quivering tambourine / you slide your hand in.’ The bodies here wrestle with the epistemological questions of the mind’s “thought-god” that wonders ‘How would a doctor classify // this work of not knowing’? Between each section we encounter a pair of empty parenthesis, enclosing nothing, just blank space, as if to remind us we cannot contain spirit, body, mind, or time. This ecstatically strange—strangely ecstatic—collection echoes not only with ‘Episcopalian canticles [that] rise up the air shaft with fish tacos’ but also with the ghosts of Vallejo, Frost, Crane, Milton, and Stevens, all sieved through a kind of ‘material substance [that] rings / with what you can’t say.’

Catherine Barnett